Every learner is familiar with the term ‘study skills.’ But not everyone really knows or understands what they are or why they matter. After all, if your grades are pretty good why you should worry about improving your study skills?

Its important because its very rare we are good at everything, and a little guidance here and there can always help.

What we have provided here are a range of approaches to learning that improve your ability to study, and to retain and recall information.

Some people are naturally good at time management but may struggle in other areas such as essay writing. Another learner may be great at taking notes but isn’t great at putting a concept into their own words. To be able to really do your best in your studies and easily demonstrate your learning, you need to spend time developing your study skills.

We also take a moment to reflect on you and your well being. Exams are stressful at the best of times, especially when they are work related. You need to make sure you are ready to take an exam, and are in the right place mentally to do so.

Disclaimer: The information collected in these pages are taken from various open source materials and combined into a format for use as a learning aid. Please refer to the References at the bottom of this page.

What are study skills

We can describe study skills as “learning how to become a more effective learner”. They enable you to study and learn more efficiently, however, they do have to be practiced and developed. During your lifetime of learning and study you will have to; learn, interpret, condense and recall huge amounts of information. Clearly the specific skill, tool or technique you will use will be determined by; your preferred learning method, topic of study, environment and the time frame you have available.

These next pages will cover:

- the 5 types of study

- how we learn

- ways to read condensing, summarising and cue methods

- how to take notes & study from books

- prioritisation visual & auditory techniques

- how to ensure you don’t miss anything out

- how to prioritise

- general study strategy

Some of these methods may be familiar to you, whilst others will not.

Baseline / Benchmark questions

In order to get a picture of your ‘starting point’ please answer the following questions.

- How do you currently study?

- Do you feel confident / competent in utilising a range of study skills and techniques?

- Do you know / have an idea about which method is most effective for your learning? for example visual (seeing), auditory (speaking & hearing) and kinaesthetic (doing)

- How would you condense your notes?

- How do you study from your books? Can you / do you recognise how to prioritise your notes?

- Are you able to adapt your style to the type of text you are reading?

- Do you know what apps and web based study aids are currently available?

1. Types of study

There are 5 main types or reasons to study. In practice you will probably combine elements of all of these:

- To gather information (formulating a complete set of notes method):

- identify the information you need to learn

- organise, condense and record this information in a format that promotes your learning

- verify the completeness & accuracy of your notes

- To learn information (moving information from short to long term memory method):

- repeated recitations of material

- flashcards – ‘hard copy / paper based’ or app / web based recall everything you can based on a keyword

- place incorrect recalls in one pile and correctly recalled ones in another

- To check learning

- identify what has and has not been learned. This type of study requires a way to self-test method – for the material you think you have learned:

- look at the main point only and recite / write everything you know

- check for accuracy

- if you recall accurately and completely 1st time you could consider this material learned

- if you recall incorrectly or incompletely you know the material has not been learned fully

- identify what has and has not been learned. This type of study requires a way to self-test method – for the material you think you have learned:

- To refresh

- prevents you from forgetting and requires regular review and reciting method

- prevent ‘fading’ of knowledge through regular material review

- you could do this independently or as part of a study group

- if you are an auditory learner, re-listen to your material 2–3 time per week

- To improve learning skills

- this is the most underdeveloped learning skill students possess method

- critically reflect on each test / exam to evaluate your study technique

- identify which study methods (e.g. diagrams, flashcards, recital, mnemonics, visual techniques) result in the correct recall of information and vice versa

- modify study skills that result in low scores / grades

Main ways to improve learning skills

There are 4 main ways in which you can improve your learning skills.

- You should apply critical reflective learning to measure and assess how effective a given method of studying is for you. Your grades and how you feel all combine to provide you with an individualised study aid tool kit.

- Break down the effectiveness of your learning skills by identifying:

- answers that were answered completely – ask yourself ‘what learning skills were used here?’

- answers that were incorrect or where you lost points – ask yourself ‘what learning skills were used here?’

- Modify / replace learning skills that resulted in lost points

- Use all the available resources you have access to, for example:

- study groups

- app/web based systems

- colleagues/lecturers

- audio options

- the tools and techniques given here

2. How do we learn?

Neil Fleming (1987) suggested that people learn through a mixture of:

- visual – seeing

- auditory – hearing

- kinesthetic – doing

The theory behind this model is that most people will have a dominant or preferred learning style. It is worthwhile noting however that some people will have a blend of all three. If you want to test your own style there are many free versions available online, or you can complete the one below.

Visual

Visual learners…

| element | description |

| learn by… | seeing |

| think in… | pictures. Vivid images help visual learner to retain information |

| they are good at… | puzzles, writing, charts, graphs, pictures, visual metaphors etc. |

Study skill options for visual leaners include:

- note taking using – charts and diagrams

- highlighting information

- colour coding and organisation of information and notes

- converting words into pictures

- visual ‘pathways’ e.g. Method of Loci / Peg System

Auditory

Auditory learners…

| element | description |

| learn by… | listening |

| think in… | words |

| they are good at… | remembering the written word, speaking, listening, storytelling, teaching, writing |

Study skill options for auditory learners include:

- recording & replaying notes

- reciting information out loud

- using analogies – verbal

- taking part in group study discussions

Kinesthetic

Kinesthetic learners…

| element | description |

| learn by… | doing, touch & movement |

| think in… | activity |

| they are good at… | hands on elements, physical activity (including coordination), acting, building, crafts |

Study skill options for kinesthetic learners include:

- making models

- using diagrams and visual condensing methods

- reciting whilst counting on fingers

- remembering or recalling whilst moving around e.g. whilst walking or running

- some kinesthetic learners prefer to study with music

NB Kinesthetic learners may find it hard to sit still for long periods of time and may get distracted.

VAK questionnaire

In order to get an idea of your learning style(s), please complete the questionnaire and scoring system below. You may have a dominant style, or a combination of all three. Answer:

- all the questions

- each with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’

- as honestly as possible

| Number | Question | Yes | No |

| 1 |

When you are describing a party/holiday to a friend, do you describe the music, sounds and noise you experienced?

|

||

| 2 |

Do you use your hands when you speak?

|

||

| 3 |

To keep up with the news/sport, do you prefer the radio or TV rather than reading a newspaper?

|

||

| 4 |

When you use a computer, do you find the visual prompts useful, e.g. the icons/pictures in the tool bars, highlights and underlines, etc.?

|

||

| 5 |

When you have to take down information, do you prefer drawing diagrams and pictures to writing notes?

|

||

| 6 |

When you play noughts and crosses or draughts, can you picture the ‘o’ and ‘x’ or counters in different positions?

|

||

| 7 |

Do you like to take objects apart and repair things, e.g. your bike, engines, etc.?

|

||

| 8 |

When you are trying to remember the spelling of a word, do you tend to jot it down a few times in different ways until you find the one which looks right?

|

||

| 9 |

When you are learning something new, do you like spoken instructions, talks and/or lectures?

|

||

| 10 |

Do you like making things?

|

||

| 11 |

When using a computer, do you find the bleeps and sounds useful to tell you that you have done something wrong or to show when you have finished something?

|

||

| 12 |

When you revise/study or are learning something new, do you like to use diagrams and/or pictures?

|

||

| 13 |

Are you quick and efficient at copying information down?

|

||

| 14 |

If something is said to you, do you usually remember it, without it being repeated?

|

||

| 15 |

In your spare time do you like doing something physically active e.g. sport, walking, gardening, etc.?

|

||

| 16 |

When you have spare time, do you like to listen to music?

|

||

| 17 |

When you are looking at a shop display, do you prefer to look around peacefully on your own?

|

||

| 18 |

Do you find it easier to remember people’s names than their faces?

|

||

| 19 |

When you spell, do you usually have to write the word down?

|

||

| 20 |

Do you like to be able to move around when you are working?

|

||

| 21 |

Do you learn to spell by saying the words out loud?

|

||

| 22 |

When you are describing a party/holiday to a friend, do you describe what people looked like, what they were wearing and the colours?

|

||

| 23 |

When starting a new task, do you like to get on and do something straight away?

|

||

| 24 |

Do you learn well by watching someone demonstrate a particular skill?

|

||

| 25 |

Does saying things out loud help you to learn?

|

||

| 26 |

Do you like showing people how to do something as opposed to writing a series of instructions?

|

||

| 27 |

Do you like role play and acting things out?

|

||

| 28 |

Do you prefer to go out and about to find information rather than sitting in the library or at your PC?

|

||

| 29 |

When you visit a shop, do you enjoy talking about the items on display, and listening to the comments of others?

|

||

| 30 |

Do you find it easy to follow a map?

|

||

| 31 |

Do you feel that one of the best ways to appreciate goods in a shop is to be able to reach out and touch them?

|

||

| 32 |

When you read a story or an article in a magazine do you picture the scene in your mind?

|

||

| 33 |

Do you tend to hum, or talk to yourself, when completing tasks?

|

||

| 34 |

Do you look at the pictures in magazines before deciding what to read?

|

||

| 35 |

When you are planning a new journey, do you like to talk to someone to find out where to go?

|

||

| 36 |

Have you always found it difficult to stay still for long and prefer generally to be active?

|

Please see below for scoring. Remember, many people have a dominant style, but you will probably use a combination of all three when learning and studying.

Circle the questions you said YES to…

| 4 | 1 | 2 |

| 6 | 3 | 5 |

| 8 | 9 | 7 |

| 12 | 11 | 10 |

| 13 | 14 | 15 |

| 17 | 16 | 19 |

| 22 | 18 | 20 |

| 24 | 21 | 23 |

| 26 | 25 | 27 |

| 30 | 29 | 28 |

| 32 | 33 | 31 |

| 34 | 35 | 36 |

| VISUAL SCORE (total circled above) |

AUDITORY SCORE (total circled above) |

KINAESTHETIC SCORE (total circled above) |

People commonly have a main preferred learning style, but this will be part of a blend of all three.

Some people have a very strong preference; other people have a more even mixture of two or less commonly, three styles.

When you know your preferred learning style(s) you understand the type of learning that best suits you. This enables you to choose the types of learning that work best for you. There is no right or wrong learning style. The point is that there are types of learning that are right for your own preferred learning style.

Please note that this is not a scientifically validated testing instrument – it is just a simple assessment tool designed to give a broad indication of your preferred learning style(s).

3. Acrostics, acronyms, analogies & mnemonics

Acrostics, Acronyms, Analogies & Mnemonics

These 4 methods are often confused, but I don’t actually think this is an issue as long as the method is right for you. But for the purposes of these study materials we will go through the differences and specifics of each. All four of these methods condense information into something that is memorable, which could be; letters, poems, text or images (in the case of visual analogies). The key is to ensure the condensing method you use is one that can be easily recalled. Therefore, try a variety of methods and see which one(s) work best for you. You could also look online as many people post ones that work for them.

Acrostics

An acrostic is an invented sequence of letters that helps you remember a poem or other text. The first letter gives you the clue to the information you need to remember or recall. The best way to explain this is to show you some examples.

Example 1 – to memorise the planets:

Sometimes its noodles, sometimes its nacho's but you get the picture.

More appropriately for pensions then:

Just remember, you are just taking the first letter of the word and making a rhyme or poem out of it.

Acronyms

An acronym is an invented combination of letters, which is pronounced as single word. Each letter is a cue or suggestion to the item you need to remember. In pensions there are many, and many have become their own versions of the same acronym e.g. CETV, SIP or SIPP etc - look here for a fuller list of most of them:

https://www.pinsentmasons.com/out-law/guides/glossary-of-pensions-terms-and-abbreviations

Acronyms can often be confused with initialism in which words are shortened to their starting letters – for example DVD or FBI. But as I said before it doesn’t really matter what you call it as long as it works for you!

Analogies

Analogies are comparisons between unlike things that have some particular things in common. Examples would include:

- the human eye is like a camera

- a heart is like a pump

- sound waves are like the circular ripples that spread from a stone dropped in water

Analogies often begin with such phrases as: “It’s just like…” “It’s the same as…” “Think of it as…” Analogies enhance and enliven descriptions, express thoughts and ideas more clearly and precisely and help connect new concepts to things that are already familiar.

- A trustee board is like a board of directors..

- A pensions fund is like a savings account..

I realise it is a little more difficult in the financial services sector to develop appropriate analogies, but its not impossible.

Mnemonics

Mnemonics are techniques for remembering information that is otherwise quite difficult to recall. A very simple example is the ‘30 days hath September’ rhyme for remembering the number of days in each calendar month.

A lot of the information we need to remember and recall is in the form of printed or written words. This can often be difficult to encode and remember when compared to other stimuli such as; images, colours, sounds, touch, emotions and language. The three fundamental principles that underlie mnemonics are:

- imagination

- association

- location

If you can use and apply a combination of these three principles you can create a powerful study system. So, lets have a look at each of these three elements in greater detail.

Imagination

This is what you use to create and strengthen the associations needed to create effective mnemonics that are potent for you. The more strongly you imagine and visualise a situation, the more effectively it will stick in your mind for later recall. The imagery you use in your mnemonics can be as vivid as you like, as long as it helps you to remember.

Association

This is the method by which you link a thing to be remembered to a way of remembering it. You can create associations by:

- Placing things on top of each other.

- Crashing things together.

- Merging images together.

- Wrapping them around each other.

- Rotating them around each other or having them dancing together.

- Linking them using the same colour, smell, shape, or feeling.

- Location

This gives you two things; a coherent context into which you can place information so that it hangs together, as well as a way of separating one mnemonic from another. For example setting one mnemonic in a particular town can separate it from a similar mnemonic set in a city. You can build the atmosphere of these places into your mnemonics to strengthen the feeling and clarity of each location.

The Memory Palace

It seems to be appropriate here to discuss a 'new' concept in learning (even though the memory palace is a device that has been used since the time of the ancient Greeks), to help encode their memories for easy retrieval. This was a time before smart devices; if you wanted information at your fingertips you had to put that information in your head. You’d do it through a process the modern memory athletes call elaborative encoding.

The general idea with most memory techniques is to change whatever boring thing is being inputted into your memory into something that is so colourful, so exciting, and so different from anything you’ve seen before that you can’t possibly forget it

The memory palace technique is about changing your memories into images placed in a familiar mental location. The idea is that you can mentally walk through your Palace looking at your memories to recall them.

They can be big or small, indoors or outdoors, real or imaginary, so long as there’s some semblance of order that links one locus to the next, and so long as they are intimately familiar

The idea is to give your memories something to hang on to. We are pretty terrible at remembering things, especially when these memories float freely in our head. But our spatial memory is actually pretty decent and when we give our memories some needed structure, we provide that missing order and context. Creating a multi-sensory experience in your head is the other part of the trick.

Now, it’s very important to try to remember this image multisensorily.

The more associative hooks a new piece of information has, the more securely it gets embedded into the network of things you already know, and the more likely it is to remain in memory

Try to animate your image so that you watch it move. Try to think of what it might smell like or feel like and make it as vivid as possible. This is you processing your image.

Let’s look at a specific example to illustrate why this works.

Say your memory palace is your home. Take a moment to conjure images and memories of that place. We are going to stick to the outside of the house.

Mentally walk from the road to your front door, try to remember as many details as possible.

Let’s imagine that your partner has asked you to pick up some dog food from the supermarket on your way home. Now put the dog food, exactly how it looked in the supermarket outside of your front door.

Got it?

Okay, now lets try to turn the dog food into something more memorable.

How about a large dog, a Great Dane, sitting on your front porch, not like a Great Dane would, but like a person would. Let’s make them exaggeratedly chewing, but we’ll make it bubble gum instead of bone. Now the Great Dane is periodically blowing gigantic bubbles, so big that you’re worried they might pop. Maybe think about what that bubble gum would smell like or the strange smell of a mixture of bubble gum and dog. What would the dog’s skin feel like? What would it feel like to have to pick bubble gum off of the dog’s face?

Four hours from now when you leave work to head home you’ll remember you had to pick something up from the supermarket.

When you take a trip to your memory palace, walk up the road to your home and gaze at your front door. What do you think you are more likely to remember?

The dog food that you see all the time or the gum chewing Great Dane we created?

A professional memory athlete will put objects in multiple places within their palaces and have more than one palace in their repertoire. Some will even design their own fictional palaces in great detail, designed specifically as a place to hang memories.

The Memory Palace is a great way to recall a variety of things, but you will still hit a hard ceiling, and that ceiling conflicts with the Herculean amount of numbers some memory competitors can remember.

4. Reading skills

To be a really effective reader you need to be able to vary your style depending on your material and it is likely that you already do this instinctively to some extent. Ask yourself how you would read:

- a blockbuster novel

- a newspaper

- a poem

- an instruction manual

When reading for pleasure you may read quickly, with few breaks and without worrying about having to recall details later. On the other hand, when consulting an instruction manual you may read only one or two paragraphs, but you read them very carefully, making sure you understand all the details. When reading complex material, since your objective is to understand it as well as possible, you will need to adapt your reading style to this purpose.

To become a flexible reader, you need to know how to select and use a reading style that is consistent with your purpose for reading. There are three important reading styles you should learn to use and each one has its own purpose – speed reading, skim reading and scanning. Knowing when and how to use these three reading styles will make you a flexible reader.

Reading materials when studying

When studying there will be many different types of material that you will need to assimilate, which could include:

- course materials

- books

- images

- audio ‘files’ / clips

- virtual learning materials

- DVD / videos

- journals

- online resources

- your own notes

The above sources of study material are usually found in 5 main themes; core, texts, suggested reading, course materials and finally other sources which may include your additional research and assignment bibliographies / references.

Speed reading

If you find it difficult to concentrate and your mind wanders when you’re studying, you could consider reading faster! If you read too slowly your thoughts can wander off on a tangent. You can easily train yourself to read more quickly, although it takes practice. To improve your reading speed you should practice:

- not reading every word

- not reading ‘aloud’ in your head

- reading in ‘fixation’ blocks

The speed reading method:

- relax

- focus

- use a ruler or index card to guide your eyes down the page of text, line by line, or, just run the end of a pen under each line

- move the pen, ruler or card smoothly across/down the page, and force your eyes to keep up

- ensure you don’t fixate on each and every word

You will be surprised how much you take in using this approach!

Skim Reading

A skimming style is most useful when you have to read a large amount of material in a short amount of time. When using the skimming style, you should identify the main ideas in each paragraph and ignore the supportive details. Because you are looking only for the main idea in each paragraph you read, a lower level of comprehension is to be expected than if you were using a more in-depth strategy. The aim of skim reading is to get the general idea, gist or overview of a texts content. The aim of this method is not to have a detailed understanding of the text. This approach is highlighted by the famous Woody Allen quote… “I read War and Peace…it’s about Russia!”

The Skimming method

- get an overview of the text through the contents page

- read the first and least sentence of each chapter, section or paragraph to see where the text is going and what it’s covering.

Scanning

Scanning is what you do when you read very quickly for a specific piece information within a larger amount of material. Since you know exactly what you are looking for, move your eyes quickly over the reading material until you locate the specific piece of information you need to find. An example would be when looking up a number in a phone book. You can use headings and titles and formatting clues – for example bold or indented text to help you hone in on what you’re looking for.

So in summary before you begin your next reading assignment, identify your purpose for reading. Decide if you are reading for a high level of comprehension, trying to get a general idea about what you are reading, or looking for specific information. Then use the reading style that is most appropriate for your reading purpose. Remember, if you are an auditory leaner you may wish to read out aloud or record your notes.

5. Condensing & summarising

Condensing and summary methods vary depending on the topic, but all involve reducing a large amount of information down into something shorter, for example; notes, images or diagrams. These methods give you a visual summary of a topic that preserves its logical structure and any linkages or inter-dependencies.

The 5 main methods that I will be looking at are:

- keywords

- tree structure

- spider diagrams

- mind maps

- concept maps

Keywords

Keywords help with memory recall by condensing large amounts of information into a single word or short phrase that is easy to remember. The key to success is to pick a word that unlocks a large amount of information.

Don’t be tempted to highlight too much text. We have all seen, or will have done it ourselves where nearly all the page has been highlighted and we believe everything is important!

Keywords methods

- read a sentence

- ask yourself “does it have a key word”?

- if no read the next sentence, if yes, highlight it or write it down

- repeat this process for the entire page / notes

- cover up your full notes and use your keywords only to write down what you can remember – this will show you how effective your keywords are

- check for effectiveness; immediately, after a few days and after a week to really test your method

Tree structure

Tree structures or diagrams allow us to see all the possible outcomes of an event and calculate their probability. Each root, branch or leaf in a tree diagram represents a possible outcome.

Types of tree diagram include:

- relationships

- family / history tree

- fault tree

- organisational chart

- work breakdown structure – for example with that seen in project management

As hinted above, a typical decision tree comprises some three main components. These are:

Root Node

It is the top-level node and represents the ultimate objective or the decision to be made. As expected, this node stays atop the entire structure, and it is from it that all the other elements flow. The manner in which this node is stated definitely has a bearing on the kind of direction that the rest will take.

Branch Node

Branches stem from the roots. They represent the various courses of action that may be taken to solve the given issue at hand. In most cases, they are indicated by the use of the arrow lines. Depending on the exact kind of decision to be made, the branch nodes may also incorporate associated costs.

Leaf Node

Leaf nodes are attached to the branch nodes. They, as we have already stated, represent the possible outcomes for each of the actions taken. These nodes are available in two main kinds. They are the circle nodes that signify the unknown outcomes or chances and the square nodes that indicate the need to make another decision. In pensions it may be that the roots are the main topic and the branches the components that make up that topic for example this is the process tree structure for safeguarded benefits:

You just choose the topic (root), break it into smaller sections (branches), expand the information from the branches (leaves).

You just choose the topic (root), break it into smaller sections (branches), expand the information from the branches (leaves).

Spider diagrams

For essay writing in particular, there is a huge benefit in having a bird’s-eye view of your subject matter. This allows you to look over all that could be said and pick out the most relevant parts, while leaving plenty of mental space for the crafting of a comprehensive and well considered argument. Spider diagrams are an excellent tool for creating an overview and remembering it crisply. They help distil complex topics onto a single memorable page by using a branching spatial organisation, colour and images.

The two primary reasons that spider diagrams are such a powerful tool are;

- that they are memorable and that the addition of colours, pictures, and simple keywords creates a spatial structure and

- image that is easy for your memory to explore.

Mind Maps

Mind maps help you to generate ideas and make associations. They are a powerful memory aid in an examination because they are visual in nature and show the relationships between component topics within an overall subject area.

They were originated in 1974 by Tony Buzan, where he discusses his influences to Leonardo da Vinci, Albert Einstein, and Joseph Donald Novak in his processing of information.

What it has produced is one of the most used mental recall products used today.

As an example, below is a mind map of the DC Pensions world produced by the Quiet Room (it can be found here):

This technique has a number of advantages:

- it enables you to see a large amount of information / thought processing on one page

- your central idea is clearly stated in the middle of the page

- you can show connections between key concepts

- additional information can be added easily

- the open ended nature of the pattern means that you may be able to make new connections

Concept Maps

The final condensing or summarising method I have identified is the concept map.

This is a way of representing relationships between ideas images or words in the same way that a road map represents the locations of highways and towns, or a circuit diagram would show the workings of an electrical appliance. In a concept map, each word or phrase connects to another, and links back to the original idea, word, or phrase. As such they are a way to develop logical thinking and study skills by revealing connections and helping you see how individual ideas form a larger picture. Concept maps were developed to enhance meaningful learning in the sciences. A well-made concept map forms from a clearly defined “focus question”. Research has shown that because concept maps are constructed to reflect organisation of the declarative memory system, they facilitate meaningful learning for those who create and use them.

6. Cue methods

The most widely used cue method is the flashcard. Nowadays these can be electronic in nature and there are many apps or sites where these can be created or downloaded (see section 15), although of course the ‘traditional’ index card style approach is just as beneficial. Which ever method you use the principle is the same:

- they are a two sided (or virtual two-sided) aid

- one side contains a cue, question, concept or even image

- the other side the ‘answer’ or expansion

One of the primary reasons for their success is they require active recall and each time this is practiced you force your brain to remember or recall information. Below are 2 examples of cue cards showing carbohydrates and Pythagoras Theory – the blue side being side one and green being side two.

7. Note taking

It is important that your notes are complete and accurate. The best way to be certain that your notes are complete and accurate is to review themas soon after the instuction/lesson as you can while the information is still fresh in your mind. As you rewrite them you should correct any errors, fill in any gaps and add any additional or supporting information as required.

A ‘side’ benefit from rewriting your notes is that it reinforces the information helping you to remember and recall it more effectively.

Rewriting your notes method

- re-read your notes two or three times before beginning to rewrite them, so that you have the ‘big picture’ in your mind

- re-write your notes in format that shows the connections and relationships between topics, concepts and key terms

- ensure what you have written makes sense and you understand it

- ascertain that the information you wrote in your notes is consistent with any corresponding information in supporting textbooks

- look for additional sources of information that will give you greater insight

- consider changing any abbreviations and symbols into complete words and statements

- highlight the most important words and concepts

- make a note of any questions you think you may need to ask in order to clarify or expand your thinking

This is all very well, but, what you really need is a way of taking really effective notes at the time rather than having to re-write them. The two main ways you can do this are by using the Skeleton Prose and Cornell Note Taking Methods.

Skeleton prose

This is the most common form of note taking. Notes are structured as a sequence of numbered points and paragraphs, with headings and indentations which resembles an essay plan. It is a useful technique for books or articles where arguments are static and built up slowly and sequentially.

The negatives of a skeleton prose are that they: are difficult to add to or amend do not indicate the relationship or connection between different parts of the argument easy to fall into the trap of coping text verbatim

The Cornell note taking system

This method of note taking was devised for students at Cornell University in the USA and has been publicised through Walter Pauk’s books on study skills for University education.

It provides you with a structured, common-sense way of making sure that you take clear notes, engage with them actively and have accurate material from which you can study or revise. It prevents you from having to laboriously recopy your notes when revising or studying – a so called ‘do it right first time’ method.

The advantages

The advantages and benefits of this note taking method can be summarised as:

- it provides a clear set of condensed key ideas you are able to engage with the material which helps recall that information at a later date your notes provide an invaluable resource when preparing for and revising for exams or further study

The method

Prior to revising/making notes:

- on a A4 sheet of paper create a summary space along the bottom

- draw a vertical line through the remaining sheet so you have 2 sections – the left hand side being a third of the space of the right

- label the left section keywords & questions

- label the right section notes

Consider having these sheets pre-printed as a blank template so can always have with you, or as an electronic document, for example word or pages. Additionally you can do any pre-reading around the topic under consideration / discussion.

During revising/making notes

- record your notes in the right hand column – you are not aiming to write everything, but rather arguments, general ideas, facts etc.

- if you use abbreviations ensure you can recall these after the event

- leave spaces so you can add to your notes or amend then afterwards

Once completed and preferably within 24 hours:

- read through your notes and add or amend anything

- produce a summary in the space you created along the bottom of the page

- write down key words and ideas in the left and column and turn these into a set of questions

- cover up your right hand column notes and test yourself as to how well you can answer the questions you composed

8. Studying from books

There are two main ways you can study from books, namely the PQRST & SQ3R methods. Both of these methods of studying focus on the key information in books. Its unique approach is that it prioritises information using a method that directly relates to how you will be asked to use that information in an exam.

PQRST

PQRST stands for:

- Preview

- Question

- Read

- Summary

- Test

P is for Preview

Look at the topic you need to learn by skimming over the main headings and points.

Q is for Question

Formulate questions that could be asked.

R is for Read

Re-read all the material, concentrating on the information that best relates to the questions you formulated in the previous step (Q is for Question).

S for the Summary

Summarise your topic in your own words. You could use any of the condensing and summarising methods we have already covered.

T is for Test

Using the questions you developed earlier answer each one in turn. Ensure you pick a whole range of questions and not just the ones that you find easy to answer!

The benefits of PQRST

The PQRST method ensures:

- information is studied in a way that directly relates to questions that may be asked

- the method can be adapted to any subject

- allows you to practice how to time your answers

- you can potentially preempt the questions you will be asked

SQ3R

A second method you can use when studying from books is the SQ3R. This 5 step technique stands for:

- Survey

- Question

- Read

- Recall

- Review

S is for Survey

Start big and then go small – survey the whole book, then the chapters and finally the paragraphs. Also look at the titles, headings, and subheadings, picture captions, charts, graphs or maps, introductory and concluding paragraphs and any summaries. The aim of this is to get the general ‘gist’ of the material.

Q is for Question

By questioning the text you turn it from an passive activity to an active one. Ask yourself:

- why are you reading this and what is it’s purpose?

- what do you already know?

- what do you want to know?

- what is new or interesting about this material?

- does this support / supplement / contradict what I already know?

Try converting the title, headings, and/or subheadings into questions. Examples of questions you could ask include:

- What do I already know about this subject?

- How does this chapter relate to the assignment question?

- How can I relate what I read to my own experiences?

R is for Read

After questioning you will be ready for the main activity of reading. This involves careful consideration of what the author is trying to convey and involves being critical as well as active.

- firstly skim read concentrating on the main ideas and general text structure

- secondly read again to make notes on the key points

- look for answers to the questions you raised in ‘Q is for Questions’

- make sure you re-read any parts which are not clear

R is for Recall

It doesn’t matter how interesting (or not!) the text is, you must make a concerted effort to recall what you read. Failure to do so will result in information being forgotten. Recalling also provides you with the opportunity to think about and assimilate what you have just read keeping the process active.

Ask yourself “can I recall all the key facts without re-reading the text”?

Try and answer questions about what you have read and/or try and summarise what you have read. This summary should be in your own words and you should consider highlighting key words and points. Also consider using a variety of senses in order to recite and recall. Seeing, hearing and saying is known as triple strength learning, whereas quadruple strength consists of; seeing, hearing, saying and writing.

R is for Review

The final step in the SQ3R method is to review the material that you have recalled in your notes. Ask yourself:

- did you understand the main principles of the argument?

- did you identify all the main points?

- are there any gaps?

Double check you haven’t missed anything of importance. There is sometimes a temptation to ‘miss out’ pieces of information and associated questions that cover areas we do not enjoy or we find hard!

SQ3R plan

Below is a sample 7 day plan for using the SQ3R method that you might like to use. Remember it can be and indeed should be adapted for your own individual needs.

Day 1

- read the text

- formulate potential questions

Day 2

- review the important points you have highlighted

- answer the questions you formulated on day 1

- make cue / flash cards – you could do this for all the questions, or just those you find difficult

- condense / summarise any other information using one of the methods described in the previous sections

Days three, four and five

Alternate between your condensing method and notes and test yourself (orally or in writing) on the questions you formulated. Add additional condensed material if required.

Days six & seven

- list the topics and subtopics each chapter / ‘chunk’ of information contains

- create a ‘map’ for each element

You will now have a summary of the whole book/module.

9. Prioritisation

When studying a common pitfall people fall into is setting out to learn everything in the order in which is was presented or delivered. However, for a variety of reasons which could include time constraints, fatigue or sheer volume of material this may not be possible, or as you will see, even desirable. So, we need a method of separating what is essential you know, i.e. what is likely to make up the majority of your exam marks, from what would be great to know if you had unlimited time and energy.

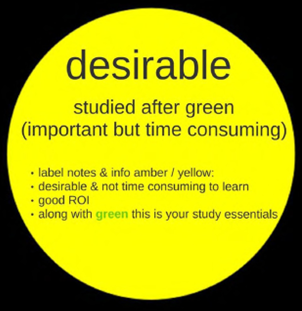

One such method is the traffic light approach.

The Traffic light Approach

Green:

Take a green pen and mark everything that is essential to know for your exam. These topics should be studied first and will allow you to progress to the less number of amber and red topics. These green areas are often found first on a syllabus and may be the easiest concepts to learn but also the easiest to underestimate.

Amber:

Take an orange, gold, or even yellow pen and label everything that is either essential to know or is not too time consuming to learn. These items will form the mainstay of your learning and range from topics leading from the green to the red range of topics.

Red:

Take a red pen and label everything you would want to know if you had unlimited time and energy. Red topics should never be studied at the expense of the essential green and desired amber topics.

Red topics would include overly complicated ideas and subjects that may add one or two marks but will cost you a great deal of time and focus. By focusing on green and amber topics those that seemed red at the start may become more amber as time goes on.

This colour system visually reminds you to get moving and motivated on green topics and discourages wasting time on red ones. Additionally it provides a progressive learning system that is logical and less likely to become ‘bogged’ down in the minutiae.

10. Visual methods

Visual study methods allow you to not only condense large amounts of info but the potential colours and images you can use provide a different sensory experience to text alone. We have seen this in previous sections for example in the case of spidergrams, mind maps, trees and concepts.

In this section we will look at two other visual ways of studying and remembering information using familiar places and the neural building of a pathway and story.

The first is The Method of Loci and for those of you who have watched Benedict Cumberbach in Sherlock Holmes, this is the method he uses in his ‘mind place’. It can also be seen in Elementary and Hannibal. The second method is that of The Peg or Hook System.

Method of Loci

The loci strategy was developed by the ancient Greeks and the word loci comes from the plural of locus, which means place. The principle of this strategy is that it is based on a familiar place, such as your home and helps you remember lists of items through organization, visualization, and association. It is particularly beneficial if you are good at picturing things in your mind.

- The Method of Loci steps:

- identify a place you are familiar

- visualise that place and all of its features

- associate each item that you need to remember with a particular feature of your place. It is worthwhile noting that the more unusual the association you make the more likely you are to remember it

- practice mentally ‘walking around’ your place and test how good your associations are and how well you can recall the information required

The best way to explain this in greater detail is by showing you a couple of examples. One a random list and another that is connected.

Examples of the Method of Loci

Example 1 – remembering 5 random items; pigeon, clown, lemon, ants, puddle. In this example the familiar place will be the kitchen. So, my pathway could be as follows:

- I walk into my kitchen

- a pigeon lands on the table

- sat at the table is a clown drinking lemonade

- in front of him is a piece of bread covered in ants and behind him the sink is overflowing creating a puddle on the floor

In this second example we will see how you can use this method to remember connected and not random information. This example uses one we looked at earlier in acrostics and it is the order of planets.

So, as with the first example you would need to set this somewhere that is familiar to you – and your pathway might be…you see a Mercury thermometer in the mouth of Venus, who is balancing a football shaped Earth on her head. On the floor is a Mars bar wrapper that has been dropped by Phil Jupitus (Jupiter), he is wearing a hat made of Saturn’s rings. You then turn round to see a chair in the shape of the Uranus symbol which Neptune sits.

Top tips

The Method of Loci is particularly powerful when relating pieces of information that are not easy connected. It does however, require an initial intensive period to practice the method and establish what kinds of visuals work for you.

Hints/Tips to help should you choose to give this method a go:

- give yourself time to practice – it’s not going to come straight away, especially if visual learning isn’t ‘your thing’

- really focus on the place you are using. Immerse yourself in everything about it – this is a highly active not passive journey

- you may find it easier to use familiar items and connections to start with and then progress to more obscure connections later

- a boring image is not going to work, it needs to be as emotionally and visually stimulating as possible

- consider using things other than images. By utilising all of your senses you are more likely to create something memorable and repeatable. So, consider smells and noises as well

The Peg / Hook System

This method works by associating the numbers 1 to 10 with words that rhyme. You can then associate these words with the information you need to remember. So, lets explain this in a little more detail. Here you can see examples of words that rhyme with numbers 1–10. Remember the words you choose will be different depending on your accent.

Example of The Peg System

As with the Method of Loci above, let’s have a look at an example so I can show you the peg system in operation.

If you wanted to remember that the Earth is the Third planet, you could visualise a image of Earth with a tree on top. Tree rhymes with 3 therefore this visual image helps you to recall that the Earth is the third planet.

Now we have looked at visual methods of studying, lets move on to auditory ones.

11. Auditory methods

We saw earlier in section 3 that people learn through a mixture of:

- visual – seeing

- auditory – hearing

- kinaesthetic – doing

You could learn from listening to:

- module summaries

- revision key points of notes

- language – if studying vocabulary

- another student

- your tutor

- audio books

- podcasts

- ‘spoken’ PDF files – there are various app available for this purpose You could also record your own notes on:

- heldheld devises – dictaphone, phone

- your computer

- plug-in microphones / headsets

- apps – text-to-speech, speech

- webreaderHD etc.

Once your audio recording has been made you can listen to it in a variety of places that includes:

- at home

- whilst travelling

- when exercising

- Pre-recording checklist

Before recording you should consider:

- checking your recording equipment – do a short test before recording a large volume of material

- ask yourself what the objective of your recording is for – for example, remembering key ‘trigger’ words or concepts in depth

- are these notes for your own use, or do you intent to share them. This will effect the quality and format you convert your recording into

- how do you want to record your information – in small ‘bite sized’ sections or a large block

12. Don't miss anything out

You would think it would go with out saying that you shouldn’t miss anything out when studying and answering questions. However, we have already seen that when revising you need to ensure the maximum ROI (return on investment).

The next two methods we will examine ensure that once you have been asked a question you consider and answer every aspect. When you combine this with the study method of predicting questions you may be asked, you will develop a robust and comprehensive study system. The methods we will be looking at are the Black Red Green and PEE.

The Black-Red-Green Method

The Black-Red-Green method was developed through the Royal Literary Fund. This method helps you to ensure that every aspect of the question that has been asked has been considered

The Black-Red-Green Method Stages

Read the question given and underline relevant parts of the question using:

- BLAck is for BLAtant instructions – something that must be done (an obvious instruction or directive)

- REd is for REference point, or REquired input. This is usually to do with definitions, terms, theories, authors etc.

- GREen is for GREmlins, or GREen lights – these are subtle signs that you could easily miss, or hints on how you should proceed or place your emphasis

PEE

Another popular method to break down and answer a question is the PEE approach:

- Point

- Evidence

- Explain

This method builds an argument around a series of logical, coherent, linked paragraphs.

The PEE Method Stages

Build an effective paragraph using:

P = Paragraph that makes one point in the right depth

E = Explanation, Evidence and Examples

E = Evaluation

You may also want to consider leaving some lines in between each paragraph in order that:

- you can add further explanation or evaluation if exam time permits

- you signal you have moved from one point onto the next

- it is easier for the marker to read

PEE Expansion

So, lets expand on explanation, evidence and examples and evaluation – the ‘E’ ‘E’. Explanation, evidence and examples These form the bulk of your paragraph and provides you with the opportunity to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of the topic being questioned.

You should construct well written, robust analysis which is written in logical, flowing sentences. One of the ways you can do this to great effect is the Seven Point Scale for Perfect Paragraphs (see below).

Evaluation

You should include evaluation in each of your paragraphs and not just the concluding one. You should ask yourself:

- how important is the point or argument you have made?

- what does your argument depend upon?

- do your sentences build on each other?

- to what extent is your argument based on facts, opinion or unreliable data?

The Seven Point Scale for Perfect Paragraphs

| Step | Explanation |

| 1 | open using words from the question to give focus |

| 2 | use relevant theory to explain and analyse the point |

| 3 | follow a logical path of analysis (use connectives) |

| 4 | use ‘hooks’ and ‘cues’ from the question to support and form your points |

| 5 | use real examples and evidence to support your point |

| 6 | come back to the question for focus |

| 7 | conclude with an evaluative statement |

Multiple choice questions

We all know that the best way to ace any exam is to study and revise lots. But, there are also some tips and techniques that can help you succeed at a tricky multiple choice exam.

1. Read very carefully

Take the time to carefully read each question and answer choice. Use a highlighter to ensure you catch words in the question like “not” and “except” that could easily trip you up. Many students choose the answer that is the opposite of the correct response simply because they miss a word, misread the question, or forget what the question is actually asking.

2. Come up with your own answer

Once you understand what the question is asking, think about what the right answer should say or contain. Use that ideal answer as a yardstick to measure the available choices. This can help you avoid falling into a trap.

3. Look for common types of wrong answers

It is hard to write a good multiple choice exam, so instructors often fall into patterns, particularly when formulating wrong-but-attractive choices. If you learn to recognize frequently used options, they will be easier to eliminate. Some common wrong answers include: reversals (for instance, the answer may feature an error in chronology, characterizing the first event as the second, or a detail that is the exact opposite of the truth), true but irrelevant (the information in the answer is true, but not relevant to the question posed), too extreme (the answer takes a fact that is true but exaggerates it to an extreme. For instance, it will insist that it is “always” true, when in reality it is only sometimes true), and getting one detail wrong (the answer is oh-so-perfect…except for one little detail that you will spend way too long obsessing about and rationalizing away).

4. Eliminate answers in two rounds

The process of elimination is central to success on multiple choice exams. In general, you want to conduct your eliminations in two rounds. During the first round, eliminate anything that is flat out wrong: the answers that contain false information, that are irrelevant to the question, etc. In a perfect world, this would lead you to one correct answer. More often than not, this leaves you with two options, over which you are likely to agonize. This is where the second round of elimination comes in. Before you obsess over your remaining answer choices, re-read the question. Remind yourself what you are looking for in a correct response. Then, compare the remaining responses. If you cannot find a difference between them, then it is likely that neither is correct and you have eliminated the correct response earlier. Usually, you will be able to find a few differences among the remaining options. So, which answer corresponds most with the course material and the question posed?

5. Do not obsess over your choices

Excessive vacillating between two answer choices is usually a waste of time. If you’re down to a couple of options, you have a 50% chance of choosing the right answer. Compare your remaining choices, isolate similarities and differences, and make a choice. Usually, multiple choice exams have lots of questions, and they are all worth the same amount. Don’t waste time obsessing over a hard question, when an easy question does just as much to raise your grade.

6. Manage your time

Before the exam begins, look at how many questions there are in the booklet and divide your time into segments. Tell yourself: “I will have completed 50 questions by the x minute mark, 70 by the y minute mark, etc.” When those time markers arise, check to see how many questions you have completed. If you are behind, start to push yourself to make quicker decisions once you’ve narrowed your choices down to two. Do not check the time after every question! This is a waste of your time. However, you need to be cognizant of the clock in order to ensure you get to all of the questions. As mentioned, usually questions are weighted equally on these types of tests, so there is little benefit to completing hard questions rather than easy ones.

7. Answer every question

If you have not completed all of the questions when there are only a couple of minutes left, pick a lucky letter and guess on all remaining questions. Depending on how many options there are for each question, you have a 20-25% of guessing correctly! And a guessed correct response is worth just as much as one that is based on careful reasoning, time management, and studying.

General rules for written answers

Here are seven ways you can ease the pressure in a written exam.

1) Find out what you have to do

One of the best ways to lose marks is to do something other than what you’ve been asked to do.

- How many questions do they want you to answer?

- How many boxes should you tick?

Every exam paper comes with instructions, so make sure you understand what the examiners are asking you to do before you get stuck in.

2) Read the questions thoroughly

Another great way to miss out on marks is to go full steam ahead without understanding the question first. What question, exactly, are you being asked to answer?

Modules are broad and varied. But exam questions are specific and narrow. Read the wording carefully so you can recall your knowledge of that exact part of the syllabus.

3) Decide on your timings

The only difference between coursework and exams is time. All the tricks that help you write a great assignment will help you in an exam too - you just have less time to perform them. Before you start writing, make a schedule. Think about how long you have, how many marks are available for each answer, and how long you should spend on each one.

4) Plan your answer

As well as working out your timings, take some time to decide what your answer is. You wouldn’t start an essay until you knew what you wanted to say - exams are no different. If you’re in an essay-based exam, plot your structure by outlining an introduction, points to argue, and a conclusion. When you do start writing, you’ll be more focused.

5) Make sure it’s relevant

A common consequence of not planning your answer is an essay full of interesting but irrelevant facts. When you write ‘on the fly’, it’s easy to brain-dump everything you know. But that’s not what the examiners want. They want a response to the specific question that’s been asked. So think about what you know, and cherry-pick the bits that are relevant.

6) Mention your sources

More often than not, your response to an exam question should be an argument based on evidence. The examiners are just as interested in the evidence as they are in the argument. Think back to your revision and reading on this topic. Which authors were important?

Use their ideas to support your answer, and make sure you name-check them.

7) Leave some space

Inspiration doesn’t always strike right away. Sometimes you need time to warm up. So if you hit a bit of a wall with one question, leave a big space and move on to the next one. This means you’ll attempt each task, and that’s a better strategy than answering just one question really well. And when you find the right ideas for an earlier question, you’ll be able to go back and add them in.

Short answer questions

Many exams and tests will have a section of short-answer questions.

The following are tried and tested tips and techniques you can use to help you get through your exam:

1. Deconstruct the question.

Identify three types of words: task words, topic words and limit words.

This list of task words will guide you on the meaning of common task words. Deconstructing a question.

2. Rephrase the question in your own words.

3. Plan the structure of your answer before starting to write.

Make sure you deconstruct the question and consider using the PEEL paragraph structure. Writing Paragraphs.

4. Use examples to give evidence and help give your writing credibility.

5. Use plain language and keep your writing straight to the point. Use the words from the question in your answer to signpost your answer for the marker.

6. Use the mark allocation to plan how much time to spend on each question.

7. Practice writing short answer responses.

Doing practice questions in exam conditions will improve your performance in the real exam.

Past exam papers are available on the PMI Learning Websites:

Advanced Diploma in Retirement Provision (ADRP)

Last update: 28 July 2025

References

The materials for this website have been collated from a number of sources:

- Apps, Jerold W. Study Skills for Adults Returning to School. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1982.

- Carney, Tom, and Barbara Carney. Liberation Learning: Self-Directed Learning for Students. Windsor, Ontario: Para-Publishing Enterprises, 1988.

- Deese, James, and Ellin K. Deese. How to Study. New York: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1969.

- Ellis, David B. Becoming a Master Student. Rapid City, South Dakota: College Survival, Inc., 1993.

- Fleet, Joan, Fiona Goodchild, and Richard Zajchowski. Successful Learning. London, Ontario: University of Western Ontario, 1987. Hanau, Laia. The Study Game. New York: Barnes & Noble Books, 1979.

- Jones, Bill, and Roy Johnson. Making the Grade. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1990.

- MacFarlane, Polly, and Sandra Hodson. Studying Effectively and Efficiently: An Integrated System. Toronto: University of Toronto, 1983.

- Nilsson, Virginia. Improve Your Study Skills. Athabasca, Alberta: Athabasca University, 1989.

- Pauk, Walter. How to Study in College. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1984.

- Robertson, Heather. Bridge to College Success. Boston, Massachusetts: Heinle & Heinle Publishers, 1991.

- Simpson, Sarah. Essential Study Skills, London, England: Bookboon, 2015.

- University of British Columbia. Strategies for Studying. Victoria, British Columbia: Orca Publishers, 1996.

- Walter, Tim, and Al Siebert. Student Success. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1987.

- Witherspoon, Del, and Eugenie Nickell. Back to School at My Age? Lanham, Maryland: University Press of America, 1991.